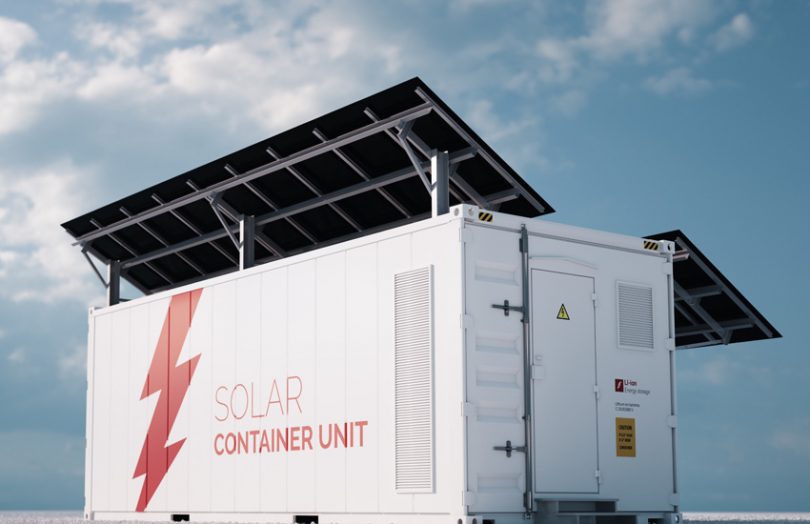

Startup Liquidstar is developing a novel solution using distributed ledger technology (DLT) to bring affordable and sustainable electrification to the rural and remote areas of the world. The solution comprises a container-based solar powered battery charging station and Internet of Things-connected portable storage batteries that are rented out to customers, with all usage and payment records managed on the blockchain.

“We liken ourselves to the Uber of electricity,” Liquidstar cofounder Scott Salandy-Defour told Ledger Insights. “We are looking at digital power stations that can be deployed anywhere to bring power to daily users or to provide emergency services in cases of disaster.”

Approximately one tenth of the world population, 789 million people, lack access to sustainable energy supplies, mainly in Africa and Asia. Much effort is being put into achieving universal access as one of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. New innovations are still needed to drive towards a target that is unlikely to be met on current trends.

Blockchain solution

Liquidstar, a spin-off from the Hong Kong blockchain research lab Chain of Things, uses the Blockpass framework, which was developed as a reusable digital identity. “We see the identity as a key for the solution and the choice of blockchain,” Salandy-Defour says. “In emerging markets, a lot of people don’t have an identity and with this we can give them a version over which they have ownership and control.”

Other features are the ability to embed a device identity, which came out of Chain of Things’ developments, and the use of data loggers embedded in the batteries with a GPS monitor for location tracking for security purposes and for monitoring their charge level.

“Trust is a big issue in these markets,” he adds. “As we evolve, we want to get more understanding of the cost of charging batteries and move to a dynamic pricing model based on the energy mix going into it. For example, batteries charged with renewable energy would be cheaper to charge than with a generator or the traditional grid and we want to price accordingly.”

Liquidstar’s business approach is to source local partners in countries of deployment, named ‘Power Rangers’, who manage the charging stations and the charging and delivery of batteries to end customers. All movements of the batteries are registered by them on the Liquidstar mobile app. Communication with end customers and their payments is via mobile text-based messaging, the minimum requirement for participation being the availability of a 2G mobile network.

Piloting projects

To date Liquidstar has completed two small pilots in Nigeria, one in the capital Lagos and the other in the south, with 20 batteries in the field and a further 20 about to be deployed. The company is also working with Benin’s government in the Smart City Benin initiative, Indonesia’s Village ministry and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) setting up projects in Kenya and Lebanon.

Additionally, late stage discussions are underway with partners in Papua New Guinea and with a local distributor in Australia to use the solution for disaster management, Salandy-Defour says.

“We estimate it will take 2-3 months to set up a project. All the products are off the shelf and the container charging stations can be readily transported by helicopter, plane or a flatbed truck. For disaster management a company can obtain one or more sets and deploy them when needed.”

One charging station should typically host about 170 batteries of different sizes providing for basic home requirements up to those of a small business. End user pricing is based on three factors, the size of the battery, how much of the charge is used and how long it is rented out. Payment is made up front, including a deposit for the battery, and any refund due – for example, for any remaining charge – is made at the end of the rental.

Development challenge

The application of blockchain is growing in emerging markets, although so far there appears to have been few successful projects that have advanced in their energy sectors.

One of these is the South Africa based Sun Exchange, which is using a blockchain platform to crowdfund and run solar PV projects. Its 30th project is currently in funding. A broadly similar approach has been taken by US-based ImpactPPA, which boasts a pipeline of projects across the globe.

Power Ledger, which launched its P2P energy trading ‘platform in urban community settings, has expanded it to rural Australia and to India among its other projects.

A 2018 white paper from the UNDP indicated that blockchain could be a valuable tool for governments, regulators, private companies and civil society to establish trust, tackle corruption and distribute resources. For the energy sector, the report highlighted that blockchain could enable both decentralized mini-grids and negative carbon tax. “Combined with renewable energy and Internet of Things, blockchain allows communities to produce their own electricity, to keep profits local and provide back-up electricity to the main grid.”

Despite this promise, UNDP itself has been involved in rather few such projects, one being the establishment by Sun Exchange of a solar power marketplace in Moldova.

“We were behind in most of the sustainable development goals indicators and need to use every tool we have, including technology, to help us get back on track,” says Robert Opp, Chief Digital Officer, UNDP. “We are testing blockchain in a range of projects. In environmental applications, blockchain has been showing promise in developing a global solution for transparent emissions verification and carbon trading.”

Clearly, there remains considerable potential for innovative blockchain offerings in emerging market energy sectors.

Micro-transactions

The next step for Liquidstar’s development is to address micro-transactions and automatic reconciliation on the blockchain, Salandy-Defour comments.

“We noticed that other players in the sector in countries such as Nigeria spend a lot of time and money processing and reconciling many thousands of small transactions, as small as 50c per day, and managing all of that can be difficult, especially when merging it with currency management. With this we will be able to reduce the costs.”

Ultimately for the end users, that will be an additional push towards improving their access to electricity.