Last week it was announced that the Delhi Forensic Science Laboratory (FSL) is using a new forensics app that is underpinned by blockchain. By using DLT it makes it harder to tamper with evidence. So far 1,500 personal have been trained to use the technology.

“The blockchain technology integrated with the e-forensic app of the Delhi FSL will ensure that evidence (material samples) submitted from the scene of crime to the FSL for analysis and reporting, remain free of human interface or interference,” said an official, according to Daily Pioneer. “Available only to authorised individuals in four separate blocks, representing four different stages of analysis, the data thus generated will be free of any tampering,”

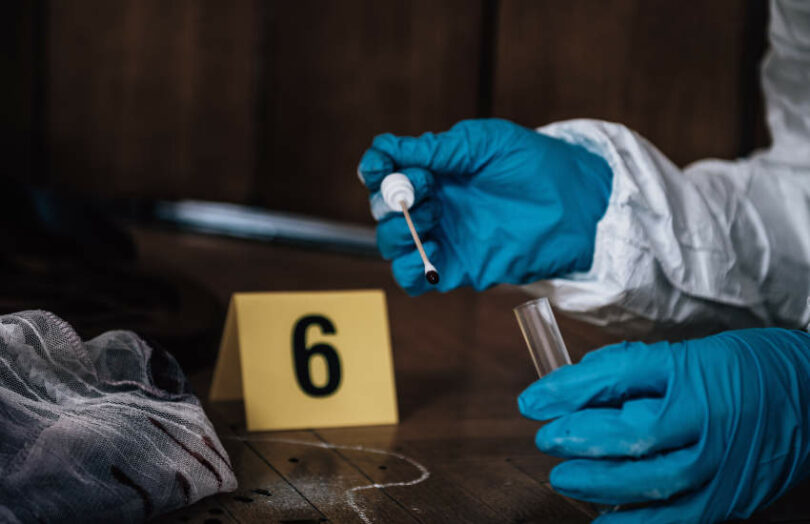

Each piece of evidence has to go through several steps from gathering it at the crime scene to storing it at the evidence locker where it’s assigned a QR code. At that point, it can be transferred to a lab where someone produces a forensics report and sends it back to the police.

While the data is encrypted, it’s unclear whether the data itself is stored on a blockchain or instead an indecipherable hash that acts like a fingerprint. Either way, if it’s an image or text it will be hard to tamper with once there’s a blockchain record. We’re a bit less convinced about how it helps with physical evidence, which we’ll come back to.

But from the sounds of it, the new app also helps to anonymize data. For example, before this system, someone doing the forensics analysis may have been aware their tests were intended to match up with a particular suspect. Now they only receive QR codes without personal information, to perform the work more objectively.

Our take: blockchain is a big value add, but not foolproof

Blockchain works well to reduce the ability to tamper with data because there are effectively multiple copies. However, it’s often interpreted as some sort of panacea that suddenly renders a process secure, when that’s not the case.

For example, at what point is the data added to the blockchain? Is it only after it arrives at the evidence locker? If so, it might be feasible to tamper with data before it gets added to the blockchain.

Arguably, in this day and age, crime scene photos should be directly transmitted from a camera to the internet and automatically sequenced and tagged to a criminal case instantly, removing the ability to delete or edit any pictures.

Photos can be entirely secure because they’re digital. Likewise, if there is an automatic log of interview evidence or notes recorded at a crime scene, they could also be tamperproof.

The two scenarios where blockchain adds less value are where there is physical handling of digital evidence before it reaches the blockchain. Or if the evidence is purely physical such as a weapon or DNA. In these cases, there’s far greater scope for corruption and interference.

If a crucial piece of physical evidence isn’t logged, how would anyone know? Is the evidence bag entirely tamperproof or could someone swap its contents, before or after it’s sealed? And it’s still entirely possible for an insider to steal the physical evidence before it reaches forensics, even if there’s a log of it. The anonymization of the data could also be broken if a police officer verbally provides additional data to a forensic analyst.

So while combining blockchain with forensics adds a level of security, it’s far from foolproof.

Meanwhile, China has been using blockchain for tracking evidence for several years. It started with cases where all the data is from the internet, such as for copyright infringement with the first criminal conviction in 2019. But it quickly evolved to broader applications similar to the Delhi scenario described here.