Today a report on central bank digital currency (CBDC) was published by the central banks of the U.S., Europe, England, Japan, Switzerland, Canada and Sweden, and the Bank for International Settlements. Nine months ago, six central banks disclosed they planned to collaborate, with the U.S. as the late joiner. None of them have as yet decided to proceed with issuing a CBDC.

The report outlines the motivations for a digital currency, as well as policy implications, features and designs. One of the more novel areas is a section on incentive designs, which includes the rather surprising suggestion that they might consider “allowing access to consumer data”.

One of the policy tradeoffs is the cost of a CBDC system and attempts to offset that cost by charging the public could discourage usage. Much like Visa and Mastercard fees that are charged to merchants, the central banks consider charging service providers.

Here’s the important part: “Decisions will be required on whether all costs are transparently charged through fees (and whether these are borne by merchants, users or both) or if some subsidisation through public funding, private cross-subsidy or allowing access to consumer data is permitted.”

Presumably, the data access is by the payment provider, who could then sell it on. And it’s rather likely that this would at least include an opt-in. But it seems the right to privacy is not considered a public good. Parallels might be drawn with the not-so-shiny aspects of Facebook and Google.

CBDC motivations

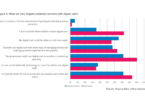

Drivers to launch a CBDC include continual access to central bank money as cash usage declines and resilience. That’s needed if there’s a failure of private payment systems, disasters, or the challenges of access in remote areas.

Increased payment diversity made it to number three on the list of motivations. But it’s hard to argue that the announcement by Facebook of its Libra plans isn’t a key driver behind the elevated interest by central banks in CBDC. Next is encouraging financial inclusion and improving cross border payments.

“Supporting public privacy” is described as a sixth motivation. While cash is entirely anonymous, for a CBDC “full anonymity is not plausible,” the paper notes. It highlights a key national policy question being details around access to the payment data.

The seventh motivation is to enable the government to make direct payments, much like U.S. proposals to use a CBDC for COVID payments.

Features and trade-offs

In terms of objectives and features, the paper says there was considerable agreement between the central banks and it succinctly describes them as:

“A CBDC must be convertible, convenient, accessible and low cost. The underlying system should be resilient, available 24/7, flexible, interoperable, private and secure for the general public. At the same time, the payment system upon which a CBDC exists and is transferred must involve the private sector to benefit from innovation and competition and support adoption and use.”

Some of the policy issues that need to be addressed include trade-offs. Perhaps the biggest is likely to be the desire by citizens to have privacy but the need to monitor to prevent money laundering as well as to reduce tax evasion. And there’s that cost trade-off mentioned already.

The paper concludes that the collaboration will continue to explore trade-offs and the G20 roadmap on cross-border payments.

Today the Bank of Japan published its own report, and the European Central Bank published one last week.