This opinion piece by HQLAᵡ’s Max Stroemer explores what history teaches about the future of collateral mobility. The views expressed are his own, not necessarily representing the opinions of HQLAᵡ or related entities.

Today, a rare alignment of technology, market enthusiasm, and political will has brought renewed focus to how cash and collateral move. And who controls that movement. At the heart of this moment is a familiar tussle between centralization and decentralization in finance.

For all the global activity around digital assets, the most consequential innovations, both technological and regulatory, are emerging from the United States. It is also where history offers the clearest lessons for institutional financiers, crypto bros, and policymakers alike.

A short history of decentralization

Alexander Hamilton designed the First Bank of the United States (1791–1811) as an early attempt to establish monetary policy in a young republic. Hamilton envisioned an institution that could unify a fledgling credit system, standardize currency issuance, and support interstate commerce. To Thomas Jefferson and his agrarian allies, it represented everything they feared: centralized financial power that eroded states’ rights. Their opposition helped ensure the Bank’s charter expired quietly, leaving the country again reliant on a patchwork of state-chartered banks.

By 1816, Congress chartered the Second Bank of the United States to restore stability after the War of 1812. Larger, more sophisticated, and more assertive than its predecessor, the Second Bank became the primary interchange of American finance. It regulated currency by redeeming state banknotes in specie, effectively policing the country’s monetary system.

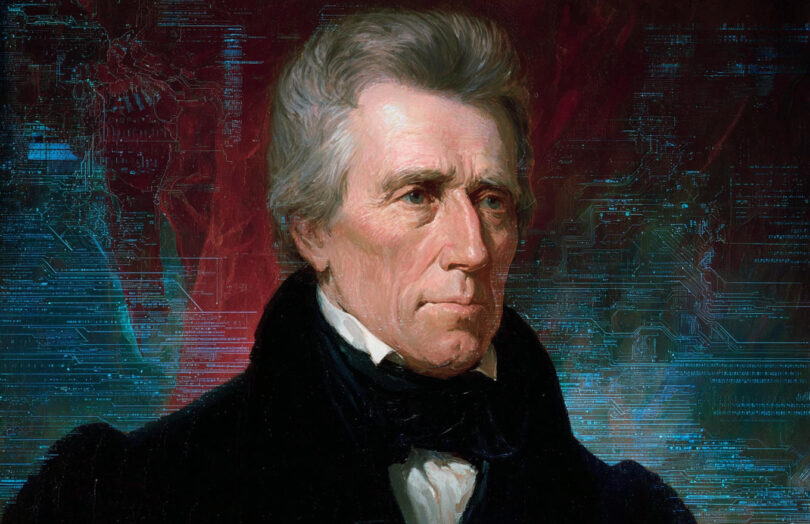

But the Bank’s power drew fire. President Andrew Jackson, convinced the Bank was corrupt, launched a scorched-earth campaign to destroy it. He vetoed its recharter in 1832, withdrew federal deposits, and denounced it as a “monster monopoly” that served the wealthy at the expense of the common citizen. “The Bank,” he declared, “is trying to kill me but I will kill it.” And he did. By 1836, the Bank was dismantled.

Jackson’s victory was decisive and destabilizing. The Free Banking Era (1837–1864) followed, a period of radical decentralization in which hundreds of state-chartered banks issued their own paper money, backed by bonds of uneven quality and subject to little meaningful oversight – leaving credit local, inconsistent, and prone to panic. In theory, these notes were redeemable and backed by collateral. In practice, they were only as trustworthy as the issuing bank’s reputation, and their value declined sharply with distance from home.

A merchant in St. Louis might hesitate to accept a Michigan note, unsure of the issuer’s solvency or the bond’s market price. If accepted at all, it came at a discount. A trader in New York might demand an even steeper haircut or refuse it entirely.

This inefficiency persisted even after the National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864. Passed primarily to fund the Civil War, the acts created demand for U.S. government bonds by allowing banks that purchased them to receive federal charters and issue national banknotes. The result was a more uniform currency but still a rigid one. And systemic risk persisted – notably in the Panic of 1907, when financier J.P. Morgan had to organize a private-sector bailout.

Recognizing that decentralized issuance required a centralized backstop, Congress created the Federal Reserve System in 1913 to provide lender-of-last-resort liquidity, an elastic money supply, and prudential oversight. In the wake of the Great Depression, this centralization intensified with the establishment of deposit insurance (FDIC) and passage of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933.

Yet even in these reforms, economists at the University of Chicago warned of a need for structural separation: “narrow banking”, where deposits would be fully backed by safe assets and insulated from credit risk. This vision lay dormant for nearly a century, waiting for a technological catalyst.

The rise of DeFi

The 2008 financial crisis rekindled distrust in centralized financial institutions. Just one year later, Bitcoin emerged as a peer-to-peer alternative, enabling users to transact directly without intermediaries. It was, arguably, a modern incarnation of the Jacksonian sentiment – a revolt against perceived elite capture of the financial system.

DeFi (Decentralized Finance) soon extended this ethos. Built on programmable smart contracts and distributed ledgers, DeFi platforms allow users to lend, borrow, and trade assets directly, bypassing traditional banks and brokers.

Stablecoins emerged as the ecosystem’s medium of exchange, replicating the unit-of-account stability of fiat on public blockchains. In structure and intent, they bear a striking resemblance to the “narrow banking” proposals of the 1930s Chicago Plan.

Policymakers around the world are responding to innovation but not in the same way. In the United States, recent political momentum is pushing for regulatory solutions that open markets. The GENIUS Act, which became U.S. law in July, and the proposed Digital Asset Market Clarity Act seek to pair legal clarity with experimentation and competition. Even the Anti-CBDC Act, which aims to block a retail digital dollar, reflects a broader desire to limit the state’s control.

The European Union is taking a discernibly different path. The Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulation prioritizes caution over speed. It imposes strict licensing, custody, and reserve requirements before allowing firms to operate. Rules limiting foreign stablecoins and the slow, state-led rollout of a digital euro reflect a more controlled, top-down technocratic approach. While the U.S. views innovation as a starting point, the EU treats it as something to be allowed – only once the safeguards are in place.

Institutional interoperability

While DeFi garners attention for its disruptive promise, a quieter revolution is underway – one focused not on retail disintermediation but institutional infrastructure.

In securities finance, reusability is everything. An instrument’s ability to fluidly deploy collateral across chains and venues determines its true value. Stablecoins currently win on mobility but lack native yield. While they can generate returns when lent out via DeFi protocols such as Aave, Morpho, or Pendle, these yields stem from secondary markets rather than the stablecoin itself. MMFs offer yield but struggle with real-time portability. Tokenized deposits offer speed but are siloed.

This is where HQLAᵡ’s Digital Collateral Record (DCR) stands out. Unlike bearer instruments or deposit tokens, DCRs represent legal title to securities held at custodians, enabling real-time ownership transfers across counterparties without the need to move securities physically. It allows for intraday repo, margining, and settlement across venues with atomic precision.

As Ethereum’s co-founder Joseph Lubin wrote in the Financial Times earlier this summer: “This is not about replacing national currencies or eliminating banks. Rather, it’s about creating interoperable layers of financial infrastructure that can coexist with existing systems and offer a path to lower friction, broader access and stronger resilience for financial systems.” This is the institutional direction of travel – not toward the anarchic decentralization of Free Banking, but toward embedded interoperability.

DCRs could be the institutional-grade glue that many DeFi proponents imagine stablecoins to be but with the trust, custody, and legal certainty required for scale.

Conclusion

The future of finance need not be a zero-sum choice between centralized trust and decentralized autonomy. History shows that too much of either breeds instability.

What matters most is the coordination function of money: its ability to clear claims and transfer ownership in a way that is efficient and scalable. DeFi has reawakened the imagination, reframing what financial infrastructure could be. But for institutions, the revolution lies not just in new tokens, but in redefining how value moves.